The United States joined the United Kingdom and Australia today in sanctioning 31-year-old Russian national Dmitry Yuryevich Khoroshev as the alleged leader of the infamous ransomware group LockBit. The U.S. Department of Justice also indicted Khoroshev and charged him with using Lockbit to attack more than 2,000 victims and extort at least $100 million in ransomware payments.

Image: U.K. National Crime Agency.

Khoroshev (Дмитрий Юрьевич Хорошев), a resident of Voronezh, Russia, was charged in a 26-count indictment by a grand jury in New Jersey.

“Dmitry Khoroshev conceived, developed, and administered Lockbit, the most prolific ransomware variant and group in the world, enabling himself and his affiliates to wreak havoc and cause billions of dollars in damage to thousands of victims around the globe,” U.S. Attorney Philip R. Sellinger said in a statement released by the Justice Department.

The indictment alleges Khoroshev acted as the LockBit ransomware group’s developer and administrator from its inception in September 2019 through May 2024, and that he typically received a 20 percent share of each ransom payment extorted from LockBit victims.

The government says LockBit victims included individuals, small businesses, multinational corporations, hospitals, schools, nonprofit organizations, critical infrastructure, and government and law-enforcement agencies.

“Khoroshev and his co-conspirators extracted at least $500 million in ransom payments from their victims and caused billions of dollars in broader losses, such as lost revenue, incident response, and recovery,” the DOJ said. “The LockBit ransomware group attacked more than 2,500 victims in at least 120 countries, including 1,800 victims in the United States.”

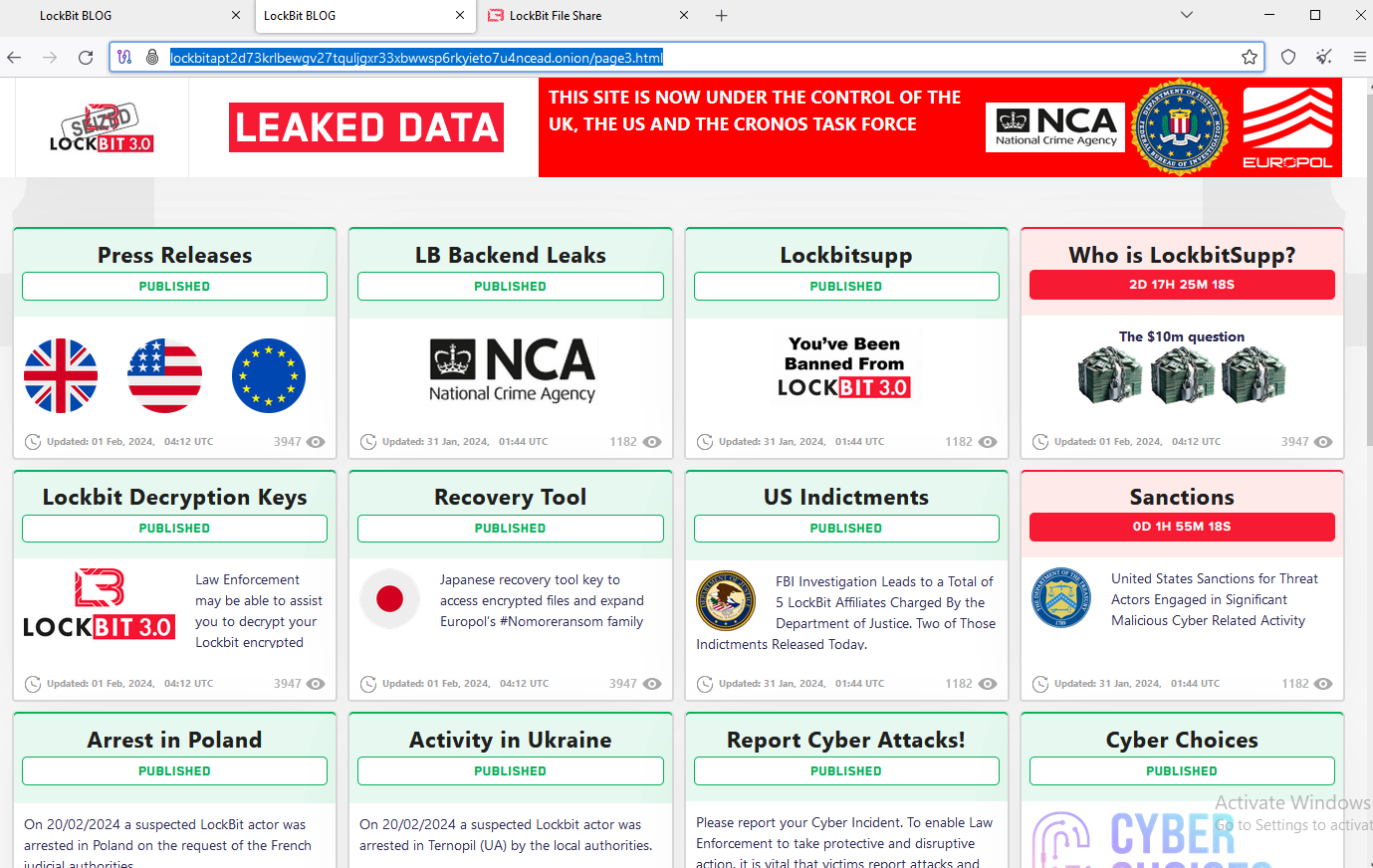

The unmasking of LockBitSupp comes nearly three months after U.S. and U.K. authorities seized the darknet websites run by LockBit, retrofitting it with press releases about the law enforcement action and free tools to help LockBit victims decrypt infected systems.

The feds used the existing design on LockBit’s victim shaming website to feature press releases and free decryption tools.

One of the blog captions that authorities left on the seized site was a teaser page that read, “Who is LockbitSupp?,” which promised to reveal the true identity of the ransomware group leader. That item featured a countdown clock until the big reveal, but when the site’s timer expired no such details were offered.

Following the FBI’s raid, LockBitSupp took to Russian cybercrime forums to assure his partners and affiliates that the ransomware operation was still fully operational. LockBitSupp also raised another set of darknet websites that soon promised to release data stolen from a number of LockBit victims ransomed prior to the FBI raid.

One of the victims LockBitSupp continued extorting was Fulton County, Ga. Following the FBI raid, LockbitSupp vowed to release sensitive documents stolen from the county court system unless paid a ransom demand before LockBit’s countdown timer expired. But when Fulton County officials refused to pay and the timer expired, no stolen records were ever published. Experts said it was likely the FBI had in fact seized all of LockBit’s stolen data.

LockBitSupp also bragged that their real identity would never be revealed, and at one point offered to pay $10 million to anyone who could discover their real name.

KrebsOnSecurity has been in intermittent contact with LockBitSupp for several months over the course of reporting on different LockBit victims. Reached at the same ToX instant messenger identity that the ransomware group leader has promoted on Russian cybercrime forums, LockBitSupp claimed the authorities named the wrong guy.

“It’s not me,” LockBitSupp replied in Russian. “I don’t understand how the FBI was able to connect me with this poor guy. Where is the logical chain that it is me? Don’t you feel sorry for a random innocent person?”

LockBitSupp, who now has a $10 million bounty for his arrest from the U.S. Department of State, has been known to be flexible with the truth. The Lockbit group routinely practiced “double extortion” against its victims — requiring one ransom payment for a key to unlock hijacked systems, and a separate payment in exchange for a promise to delete data stolen from its victims.

But Justice Department officials say LockBit never deleted its victim data, regardless of whether those organizations paid a ransom to keep the information from being published on LockBit’s victim shaming website.

Khoroshev is the sixth person officially indicted as active members of LockBit. The government says Russian national Artur Sungatov used LockBit ransomware against victims in manufacturing, logistics, insurance and other companies throughout the United States.

Ivan Gennadievich Kondratyev, a.k.a. “Bassterlord,” allegedly deployed LockBit against targets in the United States, Singapore, Taiwan, and Lebanon. Kondratyev is also charged (PDF) with three criminal counts arising from his alleged use of the Sodinokibi (aka “REvil“) ransomware variant to encrypt data, exfiltrate victim information, and extort a ransom payment from a corporate victim based in Alameda County, California.

In May 2023, U.S. authorities unsealed indictments against two alleged LockBit affiliates, Mikhail “Wazawaka” Matveev and Mikhail Vasiliev. In January 2022, KrebsOnSecurity published Who is the Network Access Broker ‘Wazawaka,’ which followed clues from Wazawaka’s many pseudonyms and contact details on the Russian-language cybercrime forums back to a 31-year-old Mikhail Matveev from Abaza, RU.

Matveev remains at large, presumably still in Russia. Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of State has a standing $10 million reward offer for information leading to Matveev’s arrest.

Vasiliev, 35, of Bradford, Ontario, Canada, is in custody in Canada awaiting extradition to the United States (the complaint against Vasiliev is at this PDF).

In June 2023, Russian national Ruslan Magomedovich Astamirov was charged in New Jersey for his participation in the LockBit conspiracy, including the deployment of LockBit against victims in Florida, Japan, France, and Kenya. Astamirov is currently in custody in the United States awaiting trial.

The Justice Department is urging victims targeted by LockBit to contact the FBI at https://lockbitvictims.ic3.gov/ to file an official complaint, and to determine whether affected systems can be successfully decrypted.

Virtual private networking (VPN) companies market their services as a way to prevent anyone from snooping on your Internet usage. But new research suggests this is a dangerous assumption when connecting to a VPN via an untrusted network, because attackers on the same network could force a target’s traffic off of the protection provided by their VPN without triggering any alerts to the user.

Image: Shutterstock.

When a device initially tries to connect to a network, it broadcasts a message to the entire local network stating that it is requesting an Internet address. Normally, the only system on the network that notices this request and replies is the router responsible for managing the network to which the user is trying to connect.

The machine on a network responsible for fielding these requests is called a Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) server, which will issue time-based leases for IP addresses. The DHCP server also takes care of setting a specific local address — known as an Internet gateway — that all connecting systems will use as a primary route to the Web.

VPNs work by creating a virtual network interface that serves as an encrypted tunnel for communications. But researchers at Leviathan Security say they’ve discovered it’s possible to abuse an obscure feature built into the DHCP standard so that other users on the local network are forced to connect to a rogue DHCP server.

“Our technique is to run a DHCP server on the same network as a targeted VPN user and to also set our DHCP configuration to use itself as a gateway,” Leviathan researchers Lizzie Moratti and Dani Cronce wrote. “When the traffic hits our gateway, we use traffic forwarding rules on the DHCP server to pass traffic through to a legitimate gateway while we snoop on it.”

The feature being abused here is known as DHCP option 121, and it allows a DHCP server to set a route on the VPN user’s system that is more specific than those used by most VPNs. Abusing this option, Leviathan found, effectively gives an attacker on the local network the ability to set up routing rules that have a higher priority than the routes for the virtual network interface that the target’s VPN creates.

“Pushing a route also means that the network traffic will be sent over the same interface as the DHCP server instead of the virtual network interface,” the Leviathan researchers said. “This is intended functionality that isn’t clearly stated in the RFC [standard]. Therefore, for the routes we push, it is never encrypted by the VPN’s virtual interface but instead transmitted by the network interface that is talking to the DHCP server. As an attacker, we can select which IP addresses go over the tunnel and which addresses go over the network interface talking to our DHCP server.”

Leviathan found they could force VPNs on the local network that already had a connection to arbitrarily request a new one. In this well-documented tactic, known as a DHCP starvation attack, an attacker floods the DHCP server with requests that consume all available IP addresses that can be allocated. Once the network’s legitimate DHCP server is completely tied up, the attacker can then have their rogue DHCP server respond to all pending requests.

“This technique can also be used against an already established VPN connection once the VPN user’s host needs to renew a lease from our DHCP server,” the researchers wrote. “We can artificially create that scenario by setting a short lease time in the DHCP lease, so the user updates their routing table more frequently. In addition, the VPN control channel is still intact because it already uses the physical interface for its communication. In our testing, the VPN always continued to report as connected, and the kill switch was never engaged to drop our VPN connection.”

The researchers say their methods could be used by an attacker who compromises a DHCP server or wireless access point, or by a rogue network administrator who owns the infrastructure themselves and maliciously configures it. Alternatively, an attacker could set up an “evil twin” wireless hotspot that mimics the signal broadcast by a legitimate provider.

Bill Woodcock is executive director at Packet Clearing House, a nonprofit based in San Francisco. Woodcock said Option 121 has been included in the DHCP standard since 2002, which means the attack described by Leviathan has technically been possible for the last 22 years.

“They’re realizing now that this can be used to circumvent a VPN in a way that’s really problematic, and they’re right,” Woodcock said.

Woodcock said anyone who might be a target of spear phishing attacks should be very concerned about using VPNs on an untrusted network.

“Anyone who is in a position of authority or maybe even someone who is just a high net worth individual, those are all very reasonable targets of this attack,” he said. “If I were trying to do an attack against someone at a relatively high security company and I knew where they typically get their coffee or sandwich at twice a week, this is a very effective tool in that toolbox. I’d be a little surprised if it wasn’t already being exploited in that way, because again this isn’t rocket science. It’s just thinking a little outside the box.”

Successfully executing this attack on a network likely would not allow an attacker to see all of a target’s traffic or browsing activity. That’s because for the vast majority of the websites visited by the target, the content is encrypted (the site’s address begins with https://). However, an attacker would still be able to see the metadata — such as the source and destination addresses — of any traffic flowing by.

KrebsOnSecurity shared Leviathan’s research with John Kristoff, founder of dataplane.org and a PhD candidate in computer science at the University of Illinois Chicago. Kristoff said practically all user-edge network gear, including WiFi deployments, support some form of rogue DHCP server detection and mitigation, but that it’s unclear how widely deployed those protections are in real-world environments.

“However, and I think this is a key point to emphasize, an untrusted network is an untrusted network, which is why you’re usually employing the VPN in the first place,” Kristoff said. “If [the] local network is inherently hostile and has no qualms about operating a rogue DHCP server, then this is a sneaky technique that could be used to de-cloak some traffic – and if done carefully, I’m sure a user might never notice.”

According to Leviathan, there are several ways to minimize the threat from rogue DHCP servers on an unsecured network. One is using a device powered by the Android operating system, which apparently ignores DHCP option 121.

Relying on a temporary wireless hotspot controlled by a cellular device you own also effectively blocks this attack.

“They create a password-locked LAN with automatic network address translation,” the researchers wrote of cellular hot-spots. “Because this network is completely controlled by the cellular device and requires a password, an attacker should not have local network access.”

Leviathan’s Moratti said another mitigation is to run your VPN from inside of a virtual machine (VM) — like Parallels, VMware or VirtualBox. VPNs run inside of a VM are not vulnerable to this attack, Moratti said, provided they are not run in “bridged mode,” which causes the VM to replicate another node on the network.

In addition, a technology called “deep packet inspection” can be used to deny all in- and outbound traffic from the physical interface except for the DHCP and the VPN server. However, Leviathan says this approach opens up a potential “side channel” attack that could be used to determine the destination of traffic.

“This could be theoretically done by performing traffic analysis on the volume a target user sends when the attacker’s routes are installed compared to the baseline,” they wrote. “In addition, this selective denial-of-service is unique as it could be used to censor specific resources that an attacker doesn’t want a target user to connect to even while they are using the VPN.”

Moratti said Leviathan’s research shows that many VPN providers are currently making promises to their customers that their technology can’t keep.

“VPNs weren’t designed to keep you more secure on your local network, but to keep your traffic more secure on the Internet,” Moratti said. “When you start making assurances that your product protects people from seeing your traffic, there’s an assurance or promise that can’t be met.”

A copy of Leviathan’s research, along with code intended to allow others to duplicate their findings in a lab environment, is available here.

The U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) today levied fines totaling nearly $200 million against the four major carriers — including AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile and Verizon — for illegally sharing access to customers’ location information without consent.

![]()

The fines mark the culmination of a more than four-year investigation into the actions of the major carriers. In February 2020, the FCC put all four wireless providers on notice that their practices of sharing access to customer location data were likely violating the law.

The FCC said it found the carriers each sold access to its customers’ location information to ‘aggregators,’ who then resold access to the information to third-party location-based service providers.

“In doing so, each carrier attempted to offload its obligations to obtain customer consent onto downstream recipients of location information, which in many instances meant that no valid customer consent was obtained,” an FCC statement on the action reads. “This initial failure was compounded when, after becoming aware that their safeguards were ineffective, the carriers continued to sell access to location information without taking reasonable measures to protect it from unauthorized access.”

The FCC’s findings against AT&T, for example, show that AT&T sold customer location data directly or indirectly to at least 88 third-party entities. The FCC found Verizon sold access to customer location data (indirectly or directly) to 67 third-party entities. Location data for Sprint customers found its way to 86 third-party entities, and to 75 third-parties in the case of T-Mobile customers.

The commission said it took action after Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) sent a letter to the FCC detailing how a company called Securus Technologies had been selling location data on customers of virtually any major mobile provider to law enforcement officials.

That same month, KrebsOnSecurity broke the news that LocationSmart — a data aggregation firm working with the major wireless carriers — had a free, unsecured demo of its service online that anyone could abuse to find the near-exact location of virtually any mobile phone in North America.

The carriers promised to “wind down” location data sharing agreements with third-party companies. But in 2019, reporting at Vice.com showed that little had changed, detailing how reporters were able to locate a test phone after paying $300 to a bounty hunter who simply bought the data through a little-known third-party service.

Sen. Wyden said no one who signed up for a cell plan thought they were giving permission for their phone company to sell a detailed record of their movements to anyone with a credit card.

“I applaud the FCC for following through on my investigation and holding these companies accountable for putting customers’ lives and privacy at risk,” Wyden said in a statement today.

The FCC fined Sprint and T-Mobile $12 million and $80 million respectively. AT&T was fined more than $57 million, while Verizon received a $47 million penalty. Still, these fines represent a tiny fraction of each carrier’s annual revenues. For example, $47 million is less than one percent of Verizon’s total wireless service revenue in 2023, which was nearly $77 billion.

The fine amounts vary because they were calculated based in part on the number of days that the carriers continued sharing customer location data after being notified that doing so was illegal (the agency also considered the number of active third-party location data sharing agreements). The FCC notes that AT&T and Verizon each took more than 320 days from the publication of the Times story to wind down their data sharing agreements; T-Mobile took 275 days; Sprint kept sharing customer location data for 386 days.

Update, 6:25 p.m. ET: Clarified that the FCC launched its investigation at the request of Sen. Wyden.